The social and industrial growth of England during the

Victorian period is generally well known, cottage industry and small mercantile

ventures were replaced with industrialisation and manufacturing on a massive,

and previously unprecedented, scale. The growth in employment opportunities in

towns and cities prompted a mass exodus from rural areas into the rapidly

industrialising towns.

The social problem novel permeates the literary output of

the Victorian period, whether a literary scholar or not, most people are

familiar with at least one novel of the period which can be said to fall into

the category of 'social problem' -from Oliver Twist to North and South the

social condition of England as a result of industrialisation and urban

expansion was firmly on the fore front of public consciousness.

By 1851 half of the population of Britain lived in towns, and by 1901

this had risen to 3/4, and it was this rapid growth which was considered the

major cause of crime, as population density in cities caused the over crowding

of slum areas and a concentration of poverty and subsistence living. The anonymity and isolationist nature of

sprawling slums precipitated and facilitated the rise of crime levels within

the jurisdiction. Without the careful

scrutiny of a smaller, and more intimately acquainted, society these masses of

the poor were inclined towards lawlessness and illegal behaviour - they were

free of what was termed 'natural policing.'

In 1852, M.D Hill (1792-1872), brother of Rowland Hill, the

postal reformer, who had been a judge in Birmingham for 30 years, was examined

by a House of Commons Committee on Juvenile crime and reported that:

A century and a half

ago...there was scarcely a large town in this island...[by a] large town I mean

[one] where an inhabitant of the humbler

classes is unknown to the majority of inhabitants...by a small town, I mean a

town where...every inhabitant is more or less known to the mass of the people

of the town...in small towns there must be a sort of natural police...operating

upon the conduct of each individual who lives, as it were, under the public

eye; but in a large town, he lives...in absolute obscurity...which to a certain

extent gives impunity.

When this is viewed in light of the content of the social

problem novel, we see it all but born out.

For example in Oliver Twist, we see a young man who's very name implies

the operation of social determinism which will make him a criminal, the name

Twist, referring to the hangman's noose which his namers believe he will

ultimately meet, and when he is exposed to the slums of London, and their many

inhabitants, he is capable of disappearing from his former masters and later

being hidden from those friends who would seek to protect him from the criminal

masses which are presented as thriving in those impoverished parts of the

city.

The social determinism, which Oliver overcomes with the

revelation that his birth and parentage are not as abject as he had been led to

believe, was considered a major motivation factor behind crime in urban

The social determinism, which Oliver overcomes with the

revelation that his birth and parentage are not as abject as he had been led to

believe, was considered a major motivation factor behind crime in urban

Few who will read

these pages have any conception of what these pestilential human rookeries [the

worst housing districts] are, where tens of thousands are crowded together amidst

horrors which call to mind what we have learned...of the slave ship...One of

the saddest results of this over-crowding is the inevitable association of

honest people with criminals...Who can wonder that every evil flourishes in

such hotbeds of vice and disease.

As already mentioned, Contemporary analysts did not believe

that it was poverty alone that caused crime, rather it was a motivating factor

which allowed latent criminal tendencies to surface. In the Report

of the Royal Commission on a Constabulary Force [1839] the social reformer

Edwin Chadwick wrote:

We have investigated

the origin of the great mass of crime committed for the sake of property, and

we find the whole ascribable to one common cause, namely, the temptations of

the profit of a career of depredation [theft], as compared with the profits of

honest and even well paid industry...the notion that any considerable

proportion of the crimes against property are cased by blameless poverty...we

find disproved at every step.

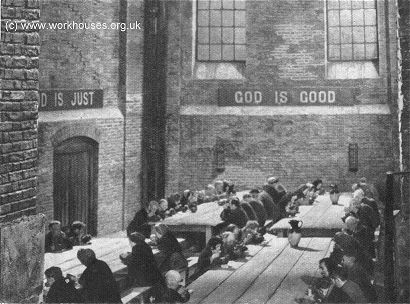

A narrow view, certainly, and an almost echoing, in tone, of

Scrooge's interrogation of the charity workers demanding 'Are there no prisons,

no poorhouses?' Assured in the expectation that the poor should voluntarily

enter such places, but it was well known to Dickens, and his socially minded

contemporaries, that these placed were often worse than the streets; with

living conditions and hygiene so poor that death and

A narrow view, certainly, and an almost echoing, in tone, of

Scrooge's interrogation of the charity workers demanding 'Are there no prisons,

no poorhouses?' Assured in the expectation that the poor should voluntarily

enter such places, but it was well known to Dickens, and his socially minded

contemporaries, that these placed were often worse than the streets; with

living conditions and hygiene so poor that death and